Academic Articles

10. “Bipartisanship on China in a Polarized America” (with Taiyi Sun), International Relations, onlinefirst, 2023.

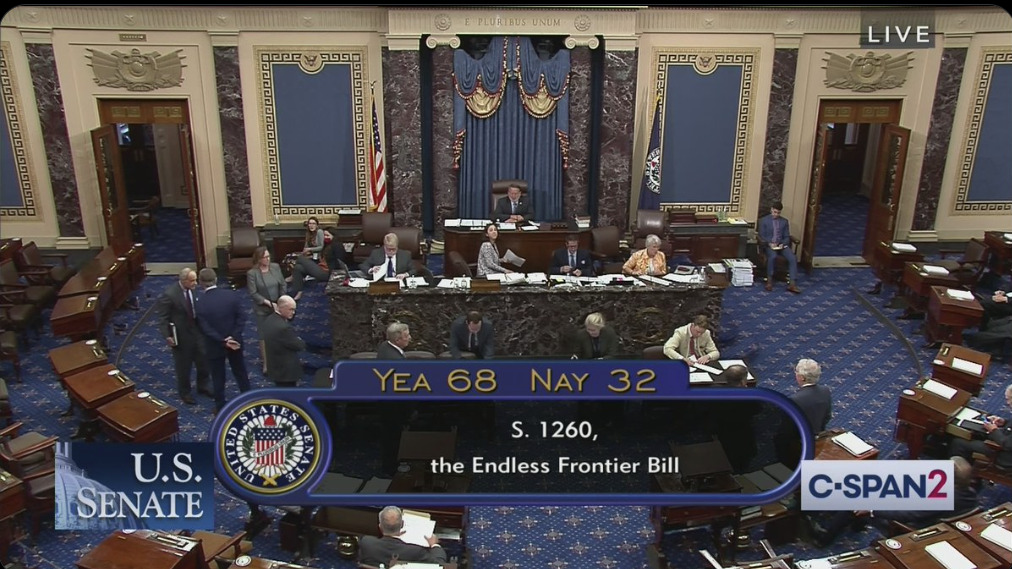

In recent years, the need for the United States to compete with and counter an increasingly assertive China has become a rare point of agreement between Democrats and Republicans, leading to a boom in China-related legislation with bipartisan support. This study asks two questions: first, whether this new China consensus is substantive or, as some analysts argue, superficial; and second, why bipartisan cooperation on China has emerged despite America’s intense political polarization. We address these two questions through a systematic analysis of China-related legislation and U.S. legislators’ messaging about China on social media. We find that the new consensus is substantive, with many bipartisan bills mandating meaningful action on trade, technology, diplomatic and military affairs, and human rights issues. Moreover, we argue that the new consensus emerged largely in 2017–2018, in response to several developments indicating China’s growing threat—geopolitical, economic, and ideological—to U.S. predominance in the international order. This study provides fresh insights on U.S.-China relations and contributes theoretically to the study of when external threats induce bipartisanship and when they do not.

9. “Does External Threat Unify? Chinese Pressure and Domestic Politics in Taiwan and South Korea,” Foreign Policy Analysis 19(1), 2023.

Since 2009, China’s growing geopolitical assertiveness has triggered or ex- acerbated conflicts with many of its neighbors. External threat is often believed to produce domestic cohesion, such as bipartisanship or a rally- ‘round-the-flag effect. However, this study uses the cases of Taiwan and South Korea to show that political parties have sometimes united around a response to Chinese pressure but at other times have been sharply divided. Despite Beijing’s aggression toward Taiwan since 2016, the Kuomintang and the Democratic Progressive Party remain at odds over cross-strait pol- icy. In contrast, South Korean conservatives and progressives united in re- sponse to Chinese economic sanctions over the deployment of Terminal High Altitude Area Defense. I argue that a country is less likely to unite against a foreign threat when a “formative rift” in its history divides polit- ical groups over national identity issues and causes them to perceive the threat differently, as in Taiwan but not South Korea. This study is based on a multilingual analysis of Taiwanese and South Korean political par- ties’ statements on China policy. Its findings contribute to scholarship on how international factors affect domestic politics and our understanding of China’s rise.

8. “Taking Authoritarian Anti-Corruption Reform Seriously,” Perspectives on Politics 20(1), 2022: 69–85.

Scholars generally assume that authoritarian regimes will not curb corruption because autocrats benefit from it politically, use anti-corruption campaigns as excuses to purge rivals, and reject democratic institutions widely thought to reduce corruption, such as judicial independence. However, I argue that authoritarian regimes curb corruption more frequently—and sometimes more effectively—than scholars realize. Using a novel scoring system for anti-corruption efforts, I find that there have been at least 25 substantial anti-corruption efforts and nine successful reforms by authoritarian regimes in recent decades. Despite the association between democracy and corruption control, successful reforms have been by fully authoritarian regimes, rather than hybrid regimes, and employed a decidedly authoritarian approach, rather than the conventional approach emphasizing democratic institutions. This authoritarian approach to corruption control commonly involves power centralization, top-down control and penetration, and regime propaganda. This essay illustrates these points with a “least likely” case study of Chinese president Xi Jinping’s controversial anti-corruption campaign. At the theoretical level, this essay suggests that authoritarian regimes succeed in overcoming challenges—corruption being a hard challenge—through their own institutional strengths, rather than by mimicking democracies. This points to the need to reconsider certain influential views in the study of authoritarianism.

7. “When Can Dictators Go It Alone? Personalism in Authoritarian Regimes” (with Andrew Leber and Matthew Reichert), Politics & Society (2022): 1–41.

Why are some autocrats able to personalize power within their regimes while others are not? While past studies have focused on the relationship between the autocrat and his or her supporting coalition of peer or subordinate elites, we find that often the crucial relationship is between the autocrat and retired leaders, party elders, and other elites of the outgoing generation. We argue that authoritarian regimes are more likely to resist a personalist takeover when members of this “old guard” retain oversight capacity over their successor, restraining him or her from overturning norms of collective rule and maximizing individual power. We illustrate this argument with case studies of attempted personalization in China and Vietnam, and use an original dataset of authoritarian leadership transitions to demonstrate its generalizability. This study introduces oversight capacity as a new concept that deepens our understanding of elite politics and inter-generational conflict in authoritarian regimes.

6. “From Corruption Control to Everything Control: The Widening Use of Inspections in Xi’s China” (with Zhang Zhu), Journal of Contemporary China 32(140), 2023: 1–18.

Under Xi Jinping, the Chinese Communist Party has dramatically expanded its use of inspections (xunshi 巡视). Existing scholarship largely portrays inspections as an anti-corruption mechanism. However, based on an examination of hundreds of post-inspection reports from party organs, provincial and municipal governments, central SOEs, and other institutions, we argue that while inspections initially focused on curbing corruption, in recent years the Xi administration has used them to advance a wide range of governance objectives. Besides curbing corruption, inspections also promote organizational management reforms, improve policy implementation, support party-building measures, and monitor loyalty to the party leadership. Our findings show the direction of political reform in China and help resolve a growing puzzle about the Xi era: how does the Xi administration simultaneously pursue both power centralization and more effective governance?

5. “The Rise and Fall of Anti-Corruption in North Korea,” Journal of East Asian Studies 22(1), 2021: 147-68.

North Korea is widely seen as having among the most corrupt governments in the world. However, the Kim family regime has not always been so accepting of government wrongdoing. Drawing on archival evidence, this study shows that Kim Il-sung saw corruption as a threat to economic development and launched campaigns to curb it throughout the 1950s. I find that these campaigns were at least somewhat successful and contributed to post-Korean War reconstruction and rapid development afterwards. So when and why did the regime shift from combating corruption to embracing it? I argue that changes in the country’s economic system following the crisis of the 1990s, especially de facto marketization, made corruption more beneficial to the regime both as a source of revenue and as an escape valve for public discontent. This study’s findings contribute to our understanding of the politics of corruption control in authoritarian regimes.

4. “The Autocrat’s Corruption Dilemma,” Government and Opposition 58(1), 2021, 22–38.

A large body of scholarship shows that autocrats can use corruption strategically to strengthen their political hold, such as by distributing rents to their supporters. However, this scholarship often overlooks how corruption may also politically damage autocrats. I argue that corruption often brings substantial political costs alongside its advantages, resulting in a ‘corruption dilemma’ for autocrats. I show that in recent years, public anger over corruption has led to numerous anti-government protests and has been a major cause of autocrats being ousted from power. How politically costly corruption is depends on factors such as the public’s tolerance for corruption, whether the autocrat is accountable to quasi-democratic institutions and whether the autocrat can credibly claim to be fighting corruption. The case of Malaysia illustrates how relying on corrupt practices to stay in power can backfire even in a long-standing authoritarian regime. My analysis advances our understanding of corruption’s mixed role in authoritarian durability and authoritarian strategies of rule.

3. “Xi’s Anti-Corruption Campaign: An All-Purpose Governing Tool,” China Leadership Monitor (67), March 2021.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s signature anti-corruption campaign has attracted attention because of its high-profile investigations and arrests, but it has also advanced government policies in areas beyond corruption control. This article discusses the campaign’s recent developments and how the party leadership has used it as an all-purpose tool for governing during Xi’s second term. Since the 19th Party Congress in 2017, the campaign has become more institutionalized and has brought down even more high-ranking officials. At the same time, the Xi administration has used anti-corruption work to support a wide range of recent policies and directives, such as the party’s anti-poverty and anti-crime initiatives. The administration’s sweeping inspections of party and state institutions have been integral to the anti-corruption campaign, but they have also aimed to improve general policy implementation, support organizational reforms, and ensure loyalty to Xi and the Chinese Communist Party. Governing through the campaign in this way has helped advance Xi’s political vision, in which a strong and disciplined party leads the country and penetrates every area of China’s state and society.

2. “The Global Rise of Corruption-Driven Political Change,” Taiwan Journal of Democracy 16(2), 2020: 147–68.

In recent years, a striking number of presidents and prime ministers around the world have been ousted before the end of their terms because of political fallout from corruption. Corruption-driven political change is an important global trend that signals the rising costs to politicians of engaging in and allowing corruption. Driven by citizens’ decreasing tolerance for wrongdoing and growing access to information, this trend is a counterpoint to recent fears that politicians are increasingly escaping accountability by spreading disinformation, polarizing society, or whipping up populist sentiments. Though ousting a corrupt leader is just one step toward the systemic reform necessary to eliminate corruption, the growth of public demands for clean government is a generally positive development for democracy. This essay analyzes dozens of cases around the world and presents a case study of the South Korean protest movement that led to President Park Geun-hye’s impeachment and removal from office in 2017.

1. "The Surprising Instability of Competitive Authoritarianism," Journal of Democracy 29.4 (2018): 129–135.

After many countries that had embarked upon transitions in the 1980s and 1990s failed to become consolidated democracies, political scientists highlighted the widespread emergence of hybrid regimes, which combine authoritarian and democratic features. Scholars argued such regimes were stable, with some positing that quasi-democratic institutions actually strengthened authoritarianism. But an examination of competitive authoritarianism (CA)—the most prominent of these hybrid types—suggests instability is the norm. Of 35 regimes identified as having been CA between 1990 and 1995, most have either democratized or been replaced by new autocracies. Furthermore, quasi-democratic institutions often contributed to CA’s breakdown. In short, hybrid regimes have not become a new form of stable nondemocratic rule.